Bahour Lake of Puducherry is not only an Important Bird Area but a heritage farming site

- SEECO

- Feb 26, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Nov 3, 2025

Bahour is the rice bowl of Puducherry a.k.a Pondicherry. It is located at 11°48'43.38"N and 79°44'47.02"E on the Coromandel Coast (Chozha-mandalam), 20 km south of Puducherry town, between Puducherry and Cuddalore as four non-contiguous enclaves within Tamilnadu plains. Though threatened by mushrooming real estate projects that have been reclaiming its wetlands, Bahour still retains its innocent rural beauty of small villages, vast paddy fields, and well managed tanks. Located in the flood plains of Pennaiyar, Bahour commune has the clay-loam soil ideal for paddy cultivation and a flood water storage recorded for more than a thousand years. Seams of lignite deposits of 8 - 15m have been discovered at 62 – 91 m depth, but cannot be extracted due to the threat of saline water intrusion in aquifers that would devastate this farming village.

A series of man-made tanks, traditionally known as Eris, were constructed in the region during the Medieval period by Pallava Kings between 4th and 9th Centuries for irrigation and flood control, and ever since they have been maintained under different rulership through community management systems. Constructed lakes/tanks colloquially known as Eris, are of two types – System Eris and Non-System Eris. A system Eri is a reinforced tank connected to a river, stream or another river-fed tank through a feeder channel for deriving water and surplus water is let out to one or more downstream tank(s) through a weir. System Eris are usually major tanks and are designed to be perennial water sources in good rainfall years. Non-system Eris are disconnected structures of seasonal nature designed to capture run off from surrounding areas thus providing local drainage, preventing gully erosion and recharging ground water. Bahour Lake is a system Eri, and is the largest and oldest of such tanks in Bahour region with a total ayacut of 1730 Ha.

History of Bahour Lake

The first mention of paddy cultivation at 'Vagur', how Bahour was known in olden times, is found in the Copper Plate inscription issued by Pallava King Nripathunga Verman in 858 AD. Vagur was also mentioned as Chathurvedi mangalam in the plates since it had a Veda education centre in 9th Century that attracted Brahmins from all directions. According to the stone inscriptions of Kannadeva, a Rashtrakuda king of 10th Centuary AD, Bahour Lake had been known as ‘Periya Eri’ or ‘the big tank’ (‘Periya’ in tamil = big/large) as well as Kadambu Eri (= Kadamb-eri) due to the presence of Neer Kadambu trees Barringtonia acutangula around the Lake (not to be confused with Mitragyna parviflora). The major source of water at Bahour Lake is flood water diverted from Pennaiyar at Sornavur dam through the 12.5 km long Bangaru vaickal (vaickal or feeder channel constructed by devadasi Bengari) and Sitheri vaickal from Sitheri bed dam across Penniyar further downstream.

Historically, lake maintenance was the responsibility of ‘eri variyam seyyum perumakkal’ who were assembly of local dalit farmers and dalit supervisors called neerkattis responsible for water distribution. Parantaka Chola -II and his successors reigned over Bahour between 10th and 13th Century AD. Inscriptions of Ganagaikonda Chozhan Rajendra -I at Sri Mulanathaswami Temple of Bahour laid down new rules in 1027 AD for annual lake maintenance, prohibiting Dalits from tank maintenance group and fixing annual ‘eri ayam’ (water tax) as quantity of paddy proportionate to land. Those aged between 10 and 80 years who failed to participate in annual eri deepening exercise were fined in gold (Kuppuswami, undated). Rashtrakuda Kingdom, Vijayanagara Dynasty and Muslim rulers (Madurai Sultanate) ruled over the region and had community-based systems (village assemblies) in place for annual tank revival and water distribution before the French administration took over.

In 1859, the French organised Caisse commune or water users commune as the decision body on water rights and maintenance which was a farmers’ union with a Government official as the presiding officer; members had to pay annual subscription fee proportional to the land owned by them. Syndicate Agricole was formed in 1911 to manage major tanks including Bahour with more powers and responsibilities vested on its president. The system of distribution of water involved diverting water of the secondary canal to the ayacut for a determined period. Inter village conflicts of water sharing were avoided by assigning an Eri and its ayacut to a respective village (Guna, 2007).

Post-independence, tanks become Government property and PWD was entrusted with the responsibility of eri maintenance. In 1970s, bore wells were introduced in the region which shifted the irrigation priority from surface water to ground water. Also, tank water irrigation was officially restricted due to practice of inland fisheries and draining off tank becomes a standard fish harvest method. Due to excess ground water extraction and collapse of traditional eri management system, many eris become lifeless, droughts become frequent and salinity intruded in ground water by 1990s. Among the three aquifers, first aquifer (shallow alluvial) dried up and second aquifer (tertiary sandstone) had saline water intrusion at 40-55m depth forcing people to sink bore well deeper below 100m. Tank Rehabilitation Project-Puducherry (TRPP) was undertaken through PWD in this scenario between 1999 and 2008 with the aid of European Union and involvement of multiple Government and Non-Government Stakeholders restoring 84 tanks in Puducherry region. Under this project, the responsibility of eri maintenance was transferred progressively to the community-based Tank Users Associations and Cluster Associations identified and formed through PWD. Tank Users Associations are also responsible for auctioning off the fish harvest.

Physiography of the Lake

Bahour Lake is a seasonal System Eri spanning 600 ha which falls mostly in Puducherry than in Tamil Nadu. Of Bahour Lake, the South, East and some of the West parts belong to Puducherry while North and remaining Westside belong to Tamil Nadu. The tank supplies water to Puducherry villages such as Aranganur, Seliamedu, Bahour Sitheri, Irulansanthai, kuruvinatham, Parikalpattu, Utchimedu, Manapattu. PiIlayarkuppam and Kirumampakkam and Tamil Nadu villages such as Karaimedu and Nagappanur. There are vast paddy fields surrounding the lake and the area is less inhabited along Puducherry side.

Climate is semi-arid and boundary vegetation is dominated by thorny scrub jungle, Acacia and Palmyra palms. The major rainy season is during north-east monsoon between October – December and is occasionally accompanied by thunder storms and cyclones when the lake also becomes full. Pennaiyar river that feeds Bahour Lake is controlled by a major irrigation Dam called Sathanar Dam located 105 km upstream in Thiruvannamalai district of Tamil Nadu. Sathanar Dam releases water for irrigation for a fixed period on reaching sufficient storage. In lean or normal monsoon years, the lake is shallow with an average depth of <1 m and large areas of perennial dry ground occupies the northern half of the wetland. This heavily silted northern part remains as a savannah constituted by grassland interspersed with Acacia nilotica throughout year where small-scale paddy cultivation is practiced by people. The lake would get fully inundated in heavy monsoon years achieving a maximum depth of 3.8 m when surplus water is released by Sathanar Dam on reaching its full capacity as in 2015 and 2016 November. It would dry up almost completely between May and September due to lack of inflow and extraction activities (irrigation, ground water extraction and fishery operations), leaving only a narrow dredged out channel along its boundaries until the next monsoon replenishes the lake. This shallow trench along its boundaries gets filled up first and dries up last. If the monsoon is deficient, the lake dries up a few months ahead and if the monsoon is in surplus, the lake dries up late than usual, depending on the reserve water quantity. In 2015 December, the lake reached maximum water level of 3.7 m, getting filled up to the brim due to heavy north-east monsoon and has been on the verge of overflowing. Subsequently, the tank has been widened in 2016 to accommodate such heavy inflow in future. However, in 2016 there was total North-East monsoon failure in the region and the lake had been dry throughout the year.

In lean monsoon years, the lake would shrink into a perennial narrow channel on the southern part of the wetland regularly deepened for fisheries operations. Eutrophication of lake water occurs due to addition of fish feed, cattle dung, detergent and agricultural runoff leading to the proliferation of aquatic vegetation like Water Hyacinth Eichhornia crassipes, Water Lily Nymphaea nouchali etc. from time to time, which are controlled through regular weeding. Emergent vegetation like Typha angustifolia and Ipomea carnea are occasionally abundant along margins which serve as foraging habitats and breeding grounds of some waterfowl like Bitterns, Rallids (Rail,Watercock, Waterhen, Moorhen etc.), Munia, Streaked Weaver etc. The bund surrounding the lake is lined with large and lofty crowned trees soon giving way to Palmyra palms on south and east direction. This boundary vegetation support both migratory and resident woodland birds. There is a reinforced concrete wall along the western boundary in Puducherry and a bund road that traverse the entire circumference of the lake.

Birds of Bahour Lake

The lake has been internationally recognized as an Important Bird Area (IBA) in 2004 since it supports more than 20,000 birds every year and had 1% of the biogeographic population of waterfowl species like Eurasian Wigeon Anas penelope and Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis as per the surveys of Jhunjhunwala and Balachandran and Alagarrajan in 1990s (Islam and Rahmani, 2004). Water bird survey in January 2014 found 49 wetland birds at Bahour lake. A seven months assessment during 2016-17 recorded 139 species of birds including forest birds despite drought conditions (Study Report of Department of Forests & Wildlife, 2017). The best bird season at Bahour is when the lake starts to dry up providing for varying extend of shallow water, marshy, swampy and grassland areas that support abundant waterfowl populations. This period usually coincides with the time of return migration and fledging season of resident waterfowl, between April and June.

In 2014, the lake started drying up early resulting in high waterfowl abundance since January. During January 2014- June 2016, good numbers of resident and migratory (M) ducks were observed, such as large congregations of Fulvous Whistling Duck Dendrocygna bicolor, Lesser Whistling Duck D. javanica, Garganey Anas querquedula (M), Spot-billed Duck A.poecilorhynca; small populations of Eurasian Wigeon A. Penelope (M), Northern Shoveller A. clypeata (M), Northern pintail A. acuta (M), Comb Duck Sarkidiornis melanotos and 1-3 individuals of Common Pochard Aythya farina (M) and Ferruginous Pochard Aythya nyroca (M).

Among other waterfowl, a few hundreds to thousands of Glossy Ibis Plegadis falcinellus, Common Coot Fulica atra, Pheasant-tailed Jacana Hydrophasianus chirurgus, Grey-headed Swamphen Porphyrio porphyrio were found regularly in summer and about a hundred individuals of Grey Heron Ardea cinereal (M), Eurasian Spoonbill Platalea leucorodia, Spot-billed Pelican Pelecanus philippensis, Painted Stork Mycteria leucocephala etc. were found when suitable habitats were available.

Bitterns such as Black bittern Dupetor flavicollis (M), Yellow Bittern Ixobrychus sinensis (M) and Chestnut Bittern Ixobrychus cinnamomeus can be found along the water hyacinth and emerging macrophytes along the lake margin. A small number of Asian Openbill Anastomus oscitans and Painted Stork Mycteria leucocephala permanently roost at the Lake.

During the migratory period of 2016-17, the lake couldn’t support much waterfowl due to drought but had good number of raptors, especially insect and small-bird eating migratory raptors like Harriers Circus spp., Common Kestrel and Falcons Falco spp. due to the vast grassland present on the dry lake bed. The Near Threatened resident raptor Red-headed Falcon Falco chicquera breeds regularly at Bahour Lake; fledging of two juveniles each were observed in both 2016 and 2017.

Other Near-Threatened species sighted at Bahour include Spot-billed Pelican, Oriental Darter Anhinga melanogaster, Painted Stork, Black-headed Ibis Threskiornis melanocephalus, White Stork Ciconia ciconia (M), Pallid Harrier Circus macrourus (M), European Roller Coracias garrulous (M), Black-tailed Godwit Limosa limosa (M) etc. Other rare/uncommon sightings reported from the lake include Spotted Redshank Tringa erythropus (M), Ruff Philomachus pugnax (M), Small Pratincole Glareola lactea (M), Oriental Pratincole G. maldivarum (M), Brown-headed Gull Larus brunnicephalus (M), White-winged Tern Chlidonias leucopterus (M), Shaheen Falcon Falco peregrinator, Amur Falcon F. amurensis(M), Pied Harrier Circus melanoleucos (M), Grey-headed Lapwing Vanellus cinereus(M), Pacific Golden Plover Pluvialis fulva (M), Red Collared Dove Streptopelia tranquebarica, Forest Wagtail Dendronanthus indicus (M), Booted Warbler Hippolais caligata (M), Jungle Prinia P.sylvatica, Thick-billed Warbler Acrocephalus aedon (M), Rosy Starling Sturnus roseu s(M), Grey-headed Starling Sturnus malabaricus (M) and Streaked Weaver Ploceus manyar.

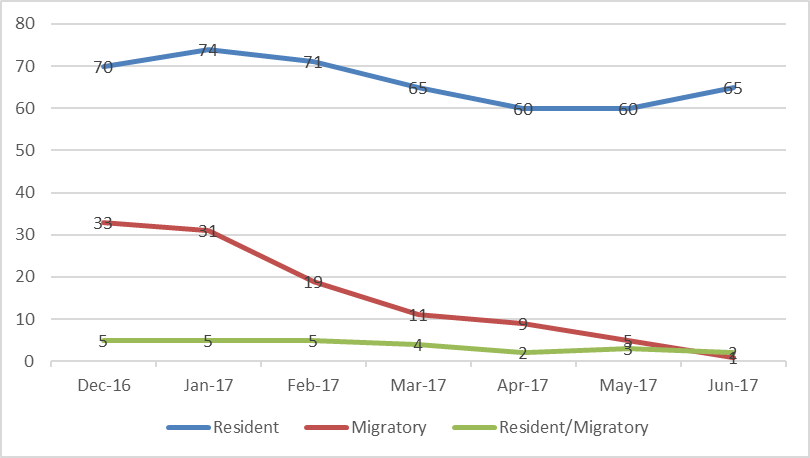

Table 1. Proportion of migratory and resident birds at Bahour Lake (Source: SEECOut Study Report, 2017)

Categories | Total No. | % |

Total bird species | 139 | 100 |

Resident | 87 | 63 |

Migratory | 46 | 33 |

Migratory /Resident | 6 | 4 |

Graph showing monthly proportion of resident and migratory birds at Bahour Lake (Source: SEECout Study Report, 2017)

Threats

Poaching is still rampant at Bahour as local community see it as an opportunity to make some quick bucks in the resident waterfowl breeding season. The most poached birds are Common Coot, Purple Moorhen, and Pheasant-tailed Jacana which can be easily baited through food, followed by Egrets, which are trapped. As much as 3,000 birds were recovered by forest department during one of the raids. (source: personal observation, local newspaper reports). Traditional bush-meat hunting mentality coupled with modern means of trapping and hunting, especially due to high demand for bushmeat from local liquor shops is driving some of the birds to their massive decline in the region.

Bahour offers important connectivity between major wetlands on the East coast. Many migrating waterfowls use this as a stop over and staging site during their annual migration. Poaching, extension of farming to the heart of the Lake bed in dry years, aquaculture and local tourism significantly affect the stop over of migrating birds and also many roosting birds abandon the site due to low safety, which will also have a cascading effect on breeding success of many nesting raptors in the area.

Paddy cultivation has become chemical intensive with the use of pesticides, herbicides and fertilizers, potentially contaminating food chains to cause biomagnificaion, affect aquatic fauna, causing shortage of food for field birds and waterfowl alike.

Outreach Efforts

SEECout has been reaching out to the school kids and local schools with information and awareness about the Backyard avian diversity of Bahour and has also been taking kids of birdwalks, building capacity among them in waterfowl identification, in an effort to train them as tour guides than poachers and also to positively associate nature with recreational as well as educational value.

The right kind of outreach has the power to change the fate of species and landscapes threatened by human activities. We all are connected at our roots to Nature. Most of the time, people are unaware of the existence of the many lifeforms or of the importance of microhabitats in their backyard. Such information may be restricted to classrooms of higher education institutions, rarely trickling down to the stakeholders whose decisions matter to the state of local biodiversity. Once the communities are informed and are encouraged to take part in activities related to biodiversity, it will grow on them, and then a movement is formed that trickle upwards from the grassroots. Then we are getting one step closer to sustainability, responsible-living, and living in harmony with nature.

Comments